In distant days of the Spice Girls, Nintendo 64s and fluorescent shell suits, one could very easily bimble their way through the English GCSEs, without giving any consideration or two-hoots to what makes for good writing. Now however, as the grammatically incompetent Bob Dylan once quoth, ‘The Times They are A-Changin’. With marks being awarded in most subjects for the quality of written expression, it is imperative that we try to remedy the situation. Therefore, this short tract, with a little help from George Orwell, will try to highlight the importance of writing eloquently and prepare you for life as a lexical champion.

I have already written on the different parts of speech and thus I presuppose that you can identify nouns, adjectives, clauses, metaphors and so on. Therefore, I will begin with Orwell’s celebrated rules of good writing before adding my emendations and additions.

The first requirement of writing is that it should be readily understandable. Clarity of written expression follows clarity of thought. If you can develop this process through excellent oracy, then so much the better. Think what you want to say, then write it as plainly as possible. Consider George Orwell’s six elementary rules from his wonderful work, Politics and the English Language:

(i) Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

(ii) Never use a long word where a short one will do.

(iii) If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

(iv) Never use the passive where you can use the active.

(v) Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

(vi) Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

These rules sound elementary, and so they are, but they demand a deep change of attitude in anyone who has grown used to writing in the style now fashionable. Let us consider each pontification and explore how they can be beneficial to our writing.

On Metaphors:

“A newly invented metaphor assists thought by evoking a visual image,” stated Orwell. Much of our language is built on metaphors without our being aware of it. As Alex Quigley explains, “Metaphors are essential for good writing. They provide the backbone to rhetoric. They are the stuff of imagination and they transform our stories. They can illuminate information and make explanations comprehensible. In short, they are essential.”

However, we need to be careful when using them. Dead metaphors can add subtlety and sophistication to your writing, but outworn metaphors should be avoided like the plague. James Geary argues that we use six metaphors a minute. His interesting and entertaining TED talk on the power and magic of metaphors can be viewed here:

On Short Words:

Use them. They are very easy to spell and even easier to understand. Do not waffle when brevity will suffice. Do not overuse polysyllabic lexis to sound like a fancy-pants. That is all.

On Unnecessary Words:

Upon occasion, additional words can add nothing but length to your writing. When using adjectives, ensure that they make your meaning more precise and be cautious of those you use to make it more emphatic. For example, very is often used to add greater detail, but leaving it out can sometimes offer more meaning and create a deeper effect. Try this: ‘He was smelly’ may have more force than ‘He was very smelly’.

Furthermore, never use three words when two spiffing ones will suffice. Remember this apology from parliamentary draftsman, Blaise Pascal ‘I have only made this letter longer because I have not had the time to make it shorter’. Proofreading and a brutal edit will make your writing concise and formal. If possible, cut out subordinate clauses and take the shortest route to the end of the sentence. Do not pass go; do not collect £200.

Finally, we come to needless repetition and tautology. Some examples include: A major disaster could have been sparked off when Morris hit the dance floor”, “The bunny died of a fatal dose of laughing gas” and “Mr Fothergill kept it from his friends that he was going on a secret and unexpected journey.” I like Mark Twain’s comments on the subject when he exclaims, “I do not find that the repetition of an important word a few times–say, three or four times–in a paragraph troubles my ear if clearness of meaning is best secured thereby. But tautological repetition which has no justifying object, but merely exposes the fact that the writer’s balance at the vocabulary bank has run short and that he is too lazy to replenish it from the thesaurus–that is another matter. It makes me feel like calling the writer to account.”

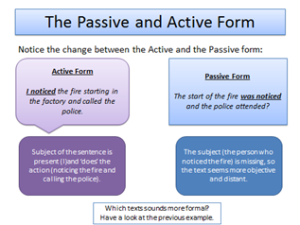

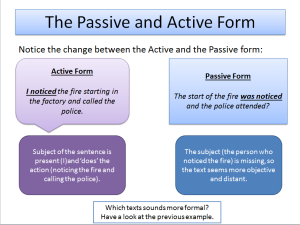

On Active, Not Passive:

The passive voice invariably hides information and sounds pompous. If unsure of the difference, please see this slide:

On Jargon and Foreign Phrases:

Avoid them as much as possible. Language from the office, bureaucracy, legal system, boring Science teachers, media trash, techy geeks, and those ruddy squaddies, should be ignored and replaced with plain and understandable expression. Keep it simple, stupid. Furthermore, do not get me started on the supercilious folk who like to drop in the odd Latin or French phrase to sound snooty. Shakespeare captures this perfectly in his bombastic and arrogant braggadocio, Pistol, when he screams “Si fortuna me tormenta, spero me contenta” to bemused prostitutes. The beautiful irony is that it’s a garbled mixture of Italian, French and Spanish, and means absolutely nothing. Shakespeare uses it to demonstrate the foolishness and faux intelligence of the character.

I hope the key messages of Orwell remain with you and help improve your writing. The more you are aware of your expression and the implicit decisions we make when trying to communicate, the more you write with clarity and sophistication.

Or not?