There is a wealth of evidence which shows that students who are widely read achieve higher grades than those who do not. Past experience here at Samuel Whitbread has proved that, in English Literature and Language at A Level, there is a clear correlation between the breadth of reading a student has undertaken and ultimate grades. Shockingly, every year, there are students who opt to study English at A Level who claim not to read at all . Without fail, these students struggle to accomplish the written tasks to the same standard as their peers who are keen readers of a variety of texts.

The benefits of reading are huge: not only does it increase your fluency in spelling, punctuation and grammar (since you unconsciously pick up correct English usage) but also you are exposed to a wide range of writing forms and styles. For example, you will find it extremely difficult to analyse the similarities and differences in different texts if you have no experience of different styles and genres. Similarly, you need to read historical articles and critical theory to enhance your argument and achieve the higher bands in your coursework.

If you intend to go on to University, whatever your course, then you will be expected to read widely in order to increase your subject knowledge. It really is foolish to embark upon an English course with the attitude that “I’m not really a reader” – NOW is the time to change that and become one.

The tasks you are expected to undertake are designed so that you will encounter a range of genres and build a portfolio fiction beyond the range you have encountered so far; furthermore, you will be expected to research and collate contextual and critical readings of texts.

Your teachers WILL check you have undertaken these tasks and this will highlight your commitment to the course.

Enjoy your reading, have a happy holidays!

Essay Texts and Topics

Complete ONE of these essay questions. Your essay must not exceed 1500 words and should include information regarding the social and cultural context of the issues. You must include quotations, analyse the language and explore the different responses of the reader or the opinion of the author. Finally, explain your own opinions on the subjects, based on any independent research you have done.

ANSWER EITHER

Question 1 on American English (AmE)

OR

Question 2 on Standard English and Varieties

OR

Question 3 on Political Correctness

Question 1

Read Text A, below, and Text B. Text A is an article published on the website MailOnline in 2010. Text B is a response sent in by a reader.

- Analyse and evaluate how these two texts use language to present ideas about the influence of American English.

- Evaluate these ideas about the influence of American English and argue your opinion of the topic. (45 marks)

Text A

Say no to the get-go! Americanisms swamping English, so wake up and smell the coffee

By MATTHEW ENGEL

Last updated at 10:01 PM on 29th May 2010

It happened early this month, shortly after the first cuckoo. I heard it, I swear I heard it. The first get-go of spring. It was on the BBC Breakfast programme on May 11: a presenter was wittering, and distinctly said that something-or-other had been clear ‘from the get-go’.

From the what?

Actually, I know all about the get-go or, worse still, the git-go. It’s an ugly Americanism, meaning ‘from the start’ or ‘from the off’. It adds nothing to Britain’s language but it’s here now, like the grey squirrel, destined to drive out native species and ravage the linguistic ecosystem.

We have to be realistic: languages grow. The success of English comes from its adaptability and the British have been borrowing words from America for at least two centuries.

Old buffers like me have always complained about the process, and we have always been defeated.

In 1832, the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge was fulminating about the ‘vile and barbarous’ new adjective that had just arrived in London. The word was ‘talented’. It sounds innocuous enough to our ears, as do ‘reliable’, ‘influential’ and ‘lengthy’, which all inspired loathing when they first crossed the Atlantic.

But the process gathered speed with the arrival of cinema and television in the 20th Century. And in the 21st it seems unstoppable. The U.S.-dominated computer industry, with its ‘licenses’, ‘colors’ and ‘favorites’ is one culprit. That ties in with mobile phones that keep ‘dialing’ numbers that are always ‘busy’.

My dictionary (a mere 12 years old) defines ‘geek’ as an American circus freak or, in Australia, ‘a good long look’. We needed a word to describe someone obsessively interested in computer technology. It seems a shame there was never any chance of coining one ourselves.

Nowadays, people have no idea where American ends and English begins. And that’s a disaster for our national self-esteem. We are in danger of subordinating our language to someone else’s – and with it large aspects of British life.

And so, hi guys, hel-LO, wake up and smell the coffee. We need to distinguish between the normal give-and-take of linguistic development and being overrun – through our own negligence and ignorance – by rampant cultural imperialism.

We are all guilty. In the weeks after 9/11 (or 11/9, as I prefer to call it), British journalists, and I was one of them, solemnly reported that the planes had been hijacked by men waving box-cutters, even though no one in Britain knew what a box-cutter was. Very few of us bothered to explain that these were what we have always called Stanley knives.

But it is time to fight back. The battle is almost uncertainly unwinnable but I am convinced there are millions of intelligent Britons out there who wince as often as I do every time they hear a witless Americanism introduced into British discourse.

Stand up and say you care. Feel free to write with your favourite horrors. Come out of the closet. Or better still, the cupboard.

EL’S TERRIBLE TEN

HOSPITALISE (or worse still hospitalize): It’s bad enough going to hospital, without being accompanied by this hideous word.

FAZE:It doesn’t faze me (even when it’s spelt ‘phase’), especially as it’s useful in Scrabble. It’s just downright irritating.

MOVIES: Can we please watch a film? Or go to the pictures? Or the flicks?

TRUCK: It deserves to get run over by a lorry.

A HIKE: Is a nice walk in the country, not a wage, price or tax rise.

THE FINGER: If I cut you up on the motorway, would you mind showing your feelings by sticking up two fingers, the British way? Thank you.

DO THE MATH: No, do the maths, for Heaven’s sake.

ROOKIES: In Britain, they are big birdies, not newcomers.

OUTAGE: An American power cut, now in use in a newspaper near you. I always read it as ‘outrage’.

MONKEY WRENCH: An adjustable spanner, if you please.

Source: http://www.dailymail.co.uk. 2010. [Accessed 20th July 2011].

Text B

Mr Engel, Please be assured that you are not alone! My pet hate is the way that any pc is configured to US English as standard. Of course it can be told to use UK English but mine have always had a tendancy to reset to US. Any other language can be removed from the memory but American is there for good. If anyone can tell me a reliable way to purge it from my pcs PLEASE post: everything I’ve tried so far says it will remove it at the next reboot but it never does.

– Harry, Huddersfield, 30/5/2010 00:49

Source: http://www.dailymail.co.uk. 2010. [Accessed 20th July 2011].

Question 2

Read Text C, below, and Text D. They are from The Queen’s English Society website and argue the need for an English Academy.

- Analyse and evaluate the ways these two texts use language to present their ideas about the use of English.

- Evaluate the ideas of the Queen’s English Society and argue your opinion of the topic. (45 marks)

Text C

Why The QES is PRESCRIPTIVIST

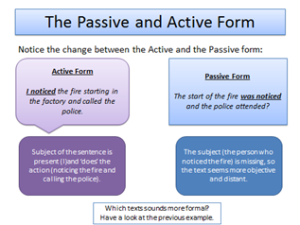

The Prescriptivists prescribe how the language should be used. They insist on the application of certain time-proven rules of usage that have developed over the ages and have been found to give the language form and style.

The Descriptivists describe how the language is used. They consider to be correct anything that is said or written. For them, if that is how the language is generally used at any given time, that is deemed to be correct English.

So fundamentally, for the Descriptivists, any liberty that is frequently and widely enough taken with the language is acceptable. The power of numbers carries the day regardless of the effect. It is fairly obvious to anyone with a “feel” for the language that the “prescriptivist” version is immeasurably less clumsy and more elegant. However, the barrier between the “descriptivist” and “prescriptivist” perception is not impermeable. Through a process of osmosis, the “prescriptivist” language, in time, absorbs elements of the “descriptivist”. This is what is loosely called the “evolution” of the language. The question is, how rapidly should this process be permitted to occur? The answer to this question is, in other languages, provided by academies of the language. Unfortunately, English has never had any such academy and that is the omission that The Queen’s English Society hopes in time to make good.

Now where does the QES stand on this issue? Consider for one moment the name of the Society — The Queen’s English Society. It is not a society that is concerned with English in all its many registers, forms and varieties although it does, for the sake of completeness, devote space to considering American English, Other English and Foreign English. This society promotes “The Queen’s English”. What is the Queen’s English? It is a form of cultured English considered to be that used by the English Monarch — formerly The King’s English, currently The Queen’s English and, at some time in the future, it will probably again become the King’s English. Certainly, our present Monarch does the language justice and Prince Charles will, if he succeeds her, continue to do so. Whether this style of English will survive the reign of Prince William is something that only a future generation will know for his speech currently carries heavy overtones of the relatively new Southern English accent known as Estuary or Essex English.

The fact remains that the QES defends The Queen’s English and therefore prescribes that style of usage. That is why even learned linguists cannot necessarily subscribe to the principles of the Queen’s English Society if they are “Descriptivists” at heart. But the QES cannot change its approach or its whole purpose would be lost and it does, at least, as it stands, provide a yardstick by which other forms of English can be measured. That is why it deserves to have “Academy” status. Once established and recognised as such, it will, from that position of authority, be able to consider how the language can be cautiously allowed to evolve in order to absorb into its accepted usage some of the innovations and deviations proposed by the “Descriptivists”.

Source: http://www.queens-english-society.com/prescriptivist.html

Text D

THE PEOPLE’S ENGLISH

IGNORANCE OR CARELESSNESS?

The Queen’s English Society devotes considerable time and effort to promoting the use of good English. It also bemoans the decline in educational standards. This is not a vain endeavour. The standard of English among the populace gives cause for grave concern.

While the Rogues’ Gallery aims to name and shame public figures, trend-setters and others who should know better, this page simply provides a number of examples of the absolutely appalling level of English used by “ordinary” people. A very revealing source of such language is the “Letters to the Editor” section on the Internet sites of some of the popular British tabloid newspapers.

It may be argued that some of the errors are just “typos” – typing errors – and that the writers would have known that they were wrong had they only reread their text. And there lies one of the reasons for the shoddy standard of written English. People are far too careless and do not reread what they have written. Everyone – even the most accomplished person – is prone to committing errors when writing but the educated person will pick up and correct those errors on rereading the text. Indeed, the author of this piece (and of many other contributions to this site) found many typos and spelling mistakes on rereading his own work which, by careful spell-checking and scrutiny, he removed before publication. This is nothing to be ashamed of – it is normal, to err is human – but to let such errors pass is inexcusable.

However, many of the worst errors are not misspellings but are gross grammatical errors – breaches of the very basic rules of English that any child should have learnt at school by the age of 15. Yet the letters that are published presumably come from persons well over that age. No-one expects or requires average citizens to be literary geniuses but a minimum level of respect for the conventions of the language – and for the readers can be expected! If a statement is worth making, it is worth making in a clear, correct and coherent manner – or it should not be made at all for the message will be lost in the medium!

Example

Original Version

how many poor hardworking people have through no fault of their own had their homes repossed in the past 12 months? how many elderly people during last winter went cold because they could’nt afford their gas bills? GREED is the word i think we are all looking for, GREED GREED GREED one of the seven deadly sins, i work many hrs on minimum wage to pay my way in this crappy country and im so glad i can sleep at night knowing that i am an honest person

Corrected version

How many poor hardworking people have, through no fault of their own, had their homes repossessed in the past 12 months? How many elderly people during last winter went cold because they couldn’t afford their gas bills? GREED is the word I think we are all looking for, GREED GREED GREED, one of the seven deadly sins. I work many hours on a minimum wage to pay my way in this crappy country and I’m so glad I can sleep at night knowing that I am an honest person.

Explanation:

Too lazy to capitalise the 1st letter of a sentence or the pronoun “I”. Spelling. Apostrophe problems: im (I’m) and could’nt (couldn’t). And punctuation just does not exist in this writer’s world

Source: http://www.queens-english-society.com/peoplesenglish.html

Question 3

Read Text E, below, and Text F. Text E is an extract from an article published in The Daily Telegraph in 2008. Text F is an article published in the Daily Mail in 2009.

- Analyse and evaluate how these two texts use language to present their ideas about the events and issues they report.

- Evaluate these ideas about politically correct language and argue your opinion of the topic. (45 marks)

Text E

The phrase Old Masters is sexist, authors and students are told

Publishers and universities are outlawing dozens of seemingly innocuous words in case they cause offence.

Banned phrases on the list, which was originally drawn up by sociologists, include Old Masters, which has been used for centuries to refer to great painters – almost all of whom were in fact male.

It is claimed that the term discriminates against women and should be replaced by “classic artists”.

The list of banned words was written by the British Sociological Association, whose members include dozens of professors, lecturers and researchers.

The list of allegedly racist words includes immigrants, developing nations and black, while so-called “disablist” terms include patient, the elderly and special needs.

It comes after one council outlawed the allegedly sexist phrase “man on the street”, and another banned staff from saying “brainstorm” in case it offended people with epilepsy. However the list of “sensitive” language is said by critics to amount to unwarranted 5 10 15 20 25 censorship and wrongly assume that people are offended by words that have been in use for years.

Prof Frank Furedi, a sociologist at the University of Kent, said he was shocked when he saw the extent of the list and how readily academics had accepted it.

“I was genuinely taken aback when I discovered that the term ‘Chinese Whisper’ was offensive because of its apparently racist connotations. I was moved to despair when I found out that one of my favourite words, ‘civilised’, ought not be used by a culturally sensitive author because of its alleged racist implications.”

Prof Furedi said that censorship is about the “policing of moral behaviour” by an army of campaign groups, teachers and media organisations who are on a “crusade” to ban certain words and promote their own politically correct alternatives.

He said people should see the efforts to ban certain words as the “coercive regulation” of everyday language and the “closing down of discussions” rather than positive attempts to protect vulnerable groups from offence.

Source: adapted from Martin BeckfordThe Daily Telegraph, 15 September 20087 H/Jan12/ENGA3

Text F

EU bans use of ‘Miss’ and ‘Mrs’ (and sportsmen and statesmen) because it claims they are sexist

Using ‘Miss’ and ‘Mrs’ has been banned by leaders of the European Union because they are not considered politically correct.

Brussels bureaucrats have decided the words are sexist and issued new guidelines in its bid to create ‘gender-neutral’ language.

The booklet warns European politicians they must avoid referring to a woman’s marital status. Instead of using the standard titles, it is asking MEPs to address women by their names.

And the rules have not stopped there – they also ban MEPs saying sportsmen and statesmen, advising athletes and political leaders should be used instead.

Man-made is also taboo – it should be artificial or synthetic, firemen is disallowed and air hostesses should be called flight attendants.

Headmasters and headmistresses must be heads or head teachers, laymen becomes layperson, and manageress or mayoress should be manager or mayor.

Police officers must be used instead of policeman and policewoman unless the officer’s sex is relevant.

The only problem words that do not fit into the guidelines are waiter and waitress, which means MEPs are at least spared one worry when ordering a coffee.

They have reacted with incredulity to the booklet, which has been sent out by the Secretary General of the European Parliament.

Scottish Tory MEP Struan Stevenson described the guidelines as ‘political correctness gone mad’.

He said: ‘This is frankly ludicrous. We’ve seen the EU institutions try to ban the bagpipes and dictate the shape of bananas, but now they seem determined to tell us which words we are entitled to use in our own language.

‘Gender-neutrality is really the last straw. The Thought Police are now on the rampage in the European Parliament.

‘We will soon be told that the use of the words “man” or “woman” has been banned in case it causes offence to those who consider ‘gender neutrality’ an essential part of life.’

West Midlands Conservative MEP Philip Bradbourn is calling on the Secretary General to reveal who authorised the publication of the booklet and how much it has cost.

He described it as ‘a waste of taxpayers’ money’ and ‘an erosion of the English language as we know it’.

‘I will have no part of it. I will continue to use my own language and expressions, which I have used all my life, and will not be instructed by this institution or anyone else in these matters,’ he said.

‘I shall also expect the many translators who sit in the European parliament to translate accurately the language I use. I find this publication offensive in the extreme.

‘The Parliament, by the publication of this document, is not only bringing itself as an institution into more disrepute than it already suffers, but it is also showing that it has succumbed to the politically correct clap‑trap currently in vogue.’

Source: Daily Mail online, 16 March 2009